Beshert

Benjamin Freedman’s photobook Beshert embodies a deeply personal exploration, informed by both the historical Jewish myth of the golem and the artist’s process of coming into his own queerness. Assuming the perspective of the golem, Freedman undergoes a photographic pilgrimage, walking the streets of historic Prague and its Jewish ghetto, where the legend takes place. Through this journey, the artist weaves together Jewish mythology and history while reflecting on his identity and sense of place within family and community. Named after the Yiddish word for “destiny,” Beshert creates a subtle, nonlinear narrative collapsing past and present, and blurs the line between acute intimacy and the monumentality of myth.

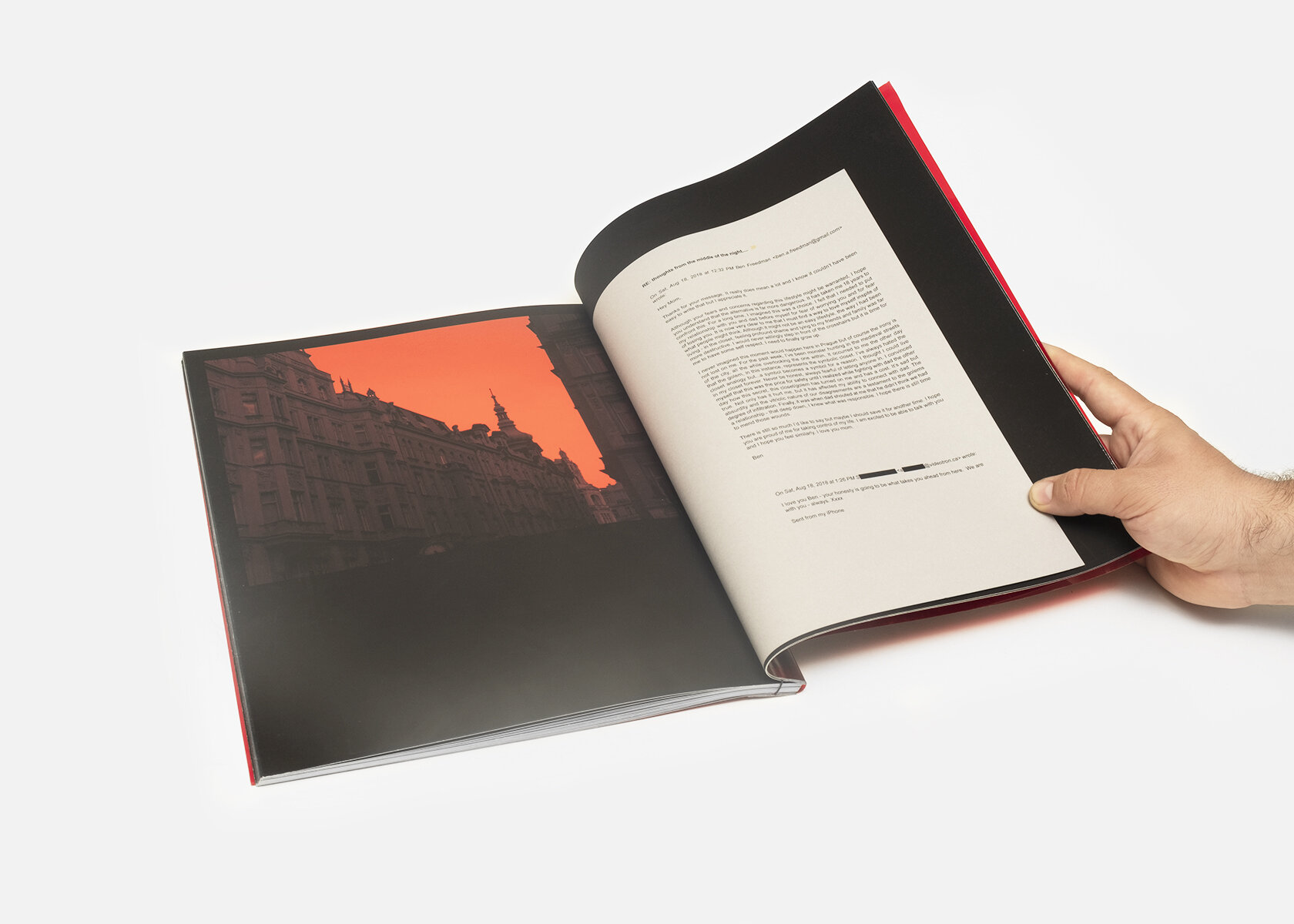

The book opens to an intimate email addressed to the artist by his mother, expressing her support about his having just “come out” as a gay man. She touches upon the struggle between Freedman and his father, however, which sets a tone of unease without resolution that informs the reading of the images that follow. Further, the letter foreshadows the convergence of meaning in the artist’s voyage to Prague, his engagement with the myth of the golem, and the evolution of his own identity. The sixteenth-century legend tells of the real-life scholar and mystic Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, who was said to have constructed the creature from clay. Created in response to pogroms and blood libels, the golem was charged with the protection of the Jewish people living within the Josefov ghetto, but ultimately turned against them. Many artists have explored the motivation behind the golem’s vengeful turn; in Freedman’s interpretation, the creature is overcome by anguish over the clash between his desire for self-determination and his inborn servitude and powerlessness. In the end, the golem was destroyed by his creator, who could not allow him autonomy.

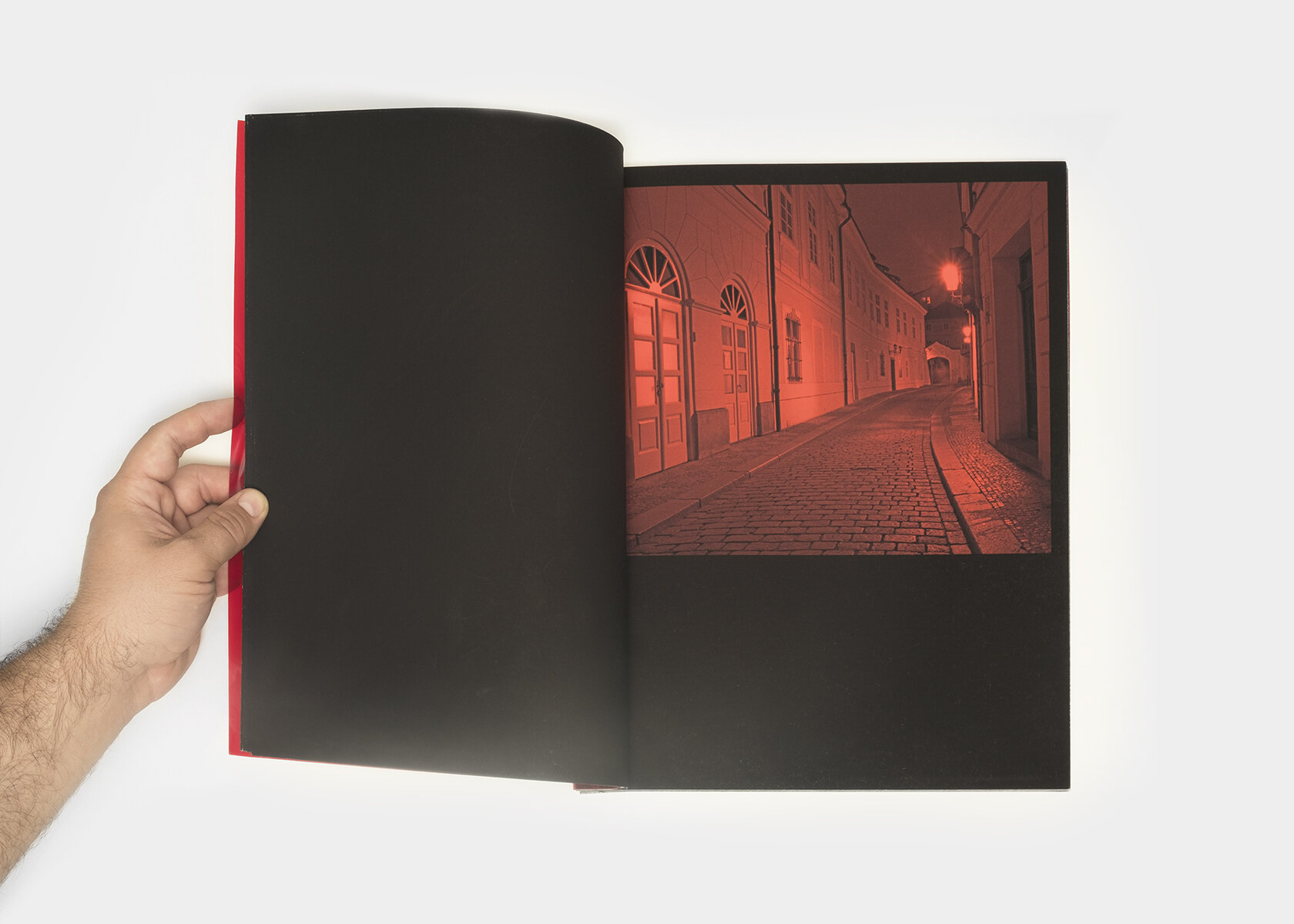

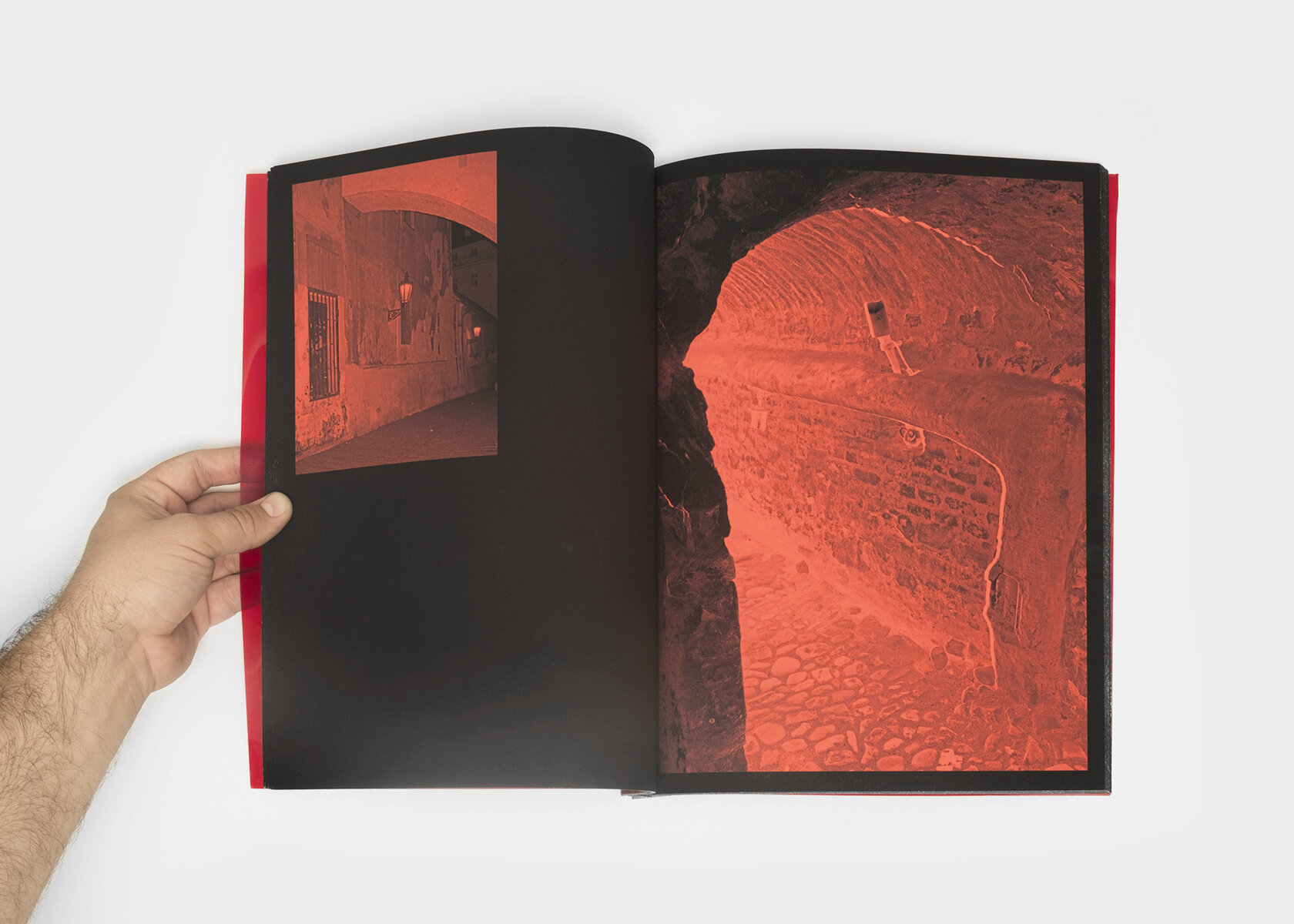

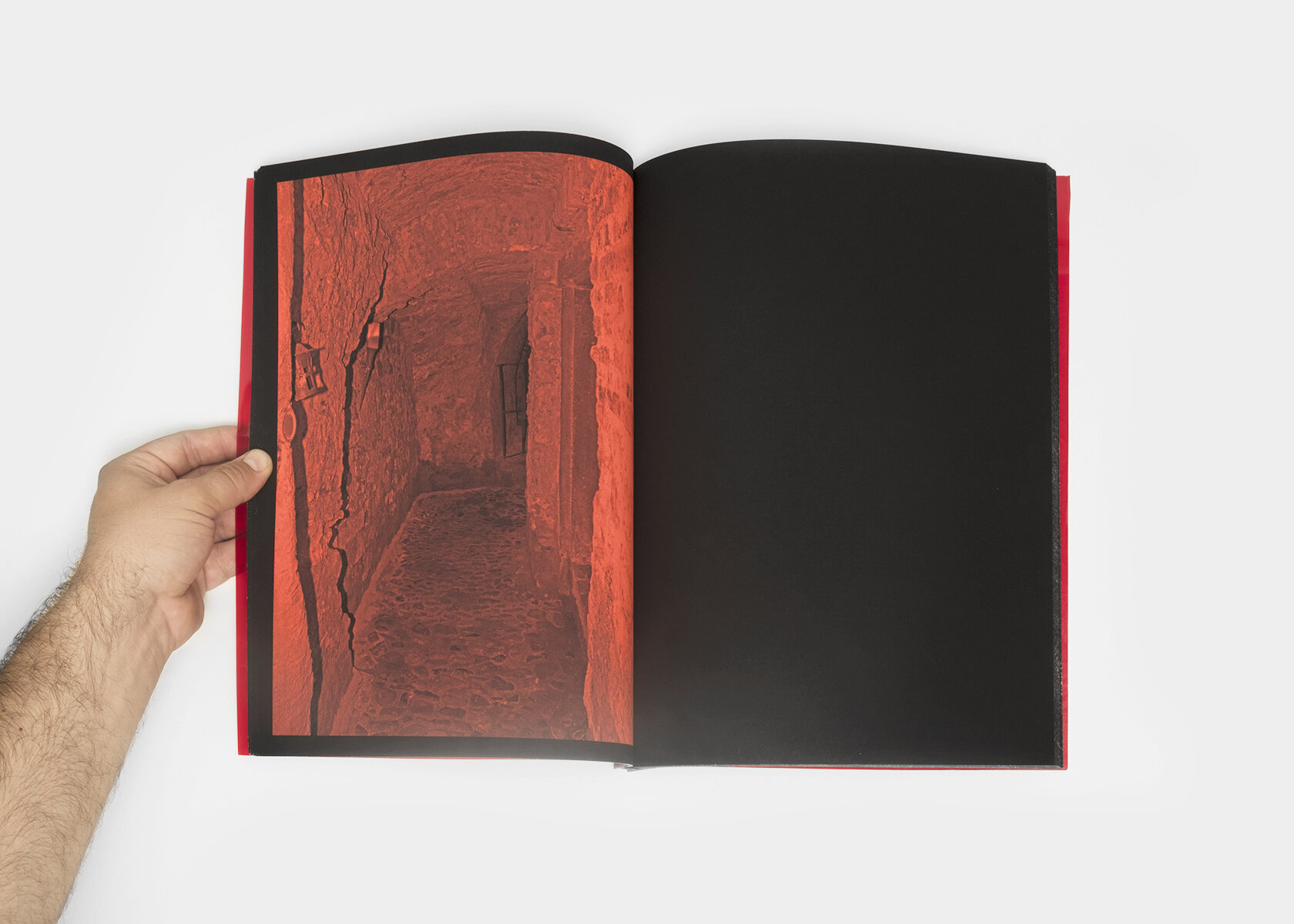

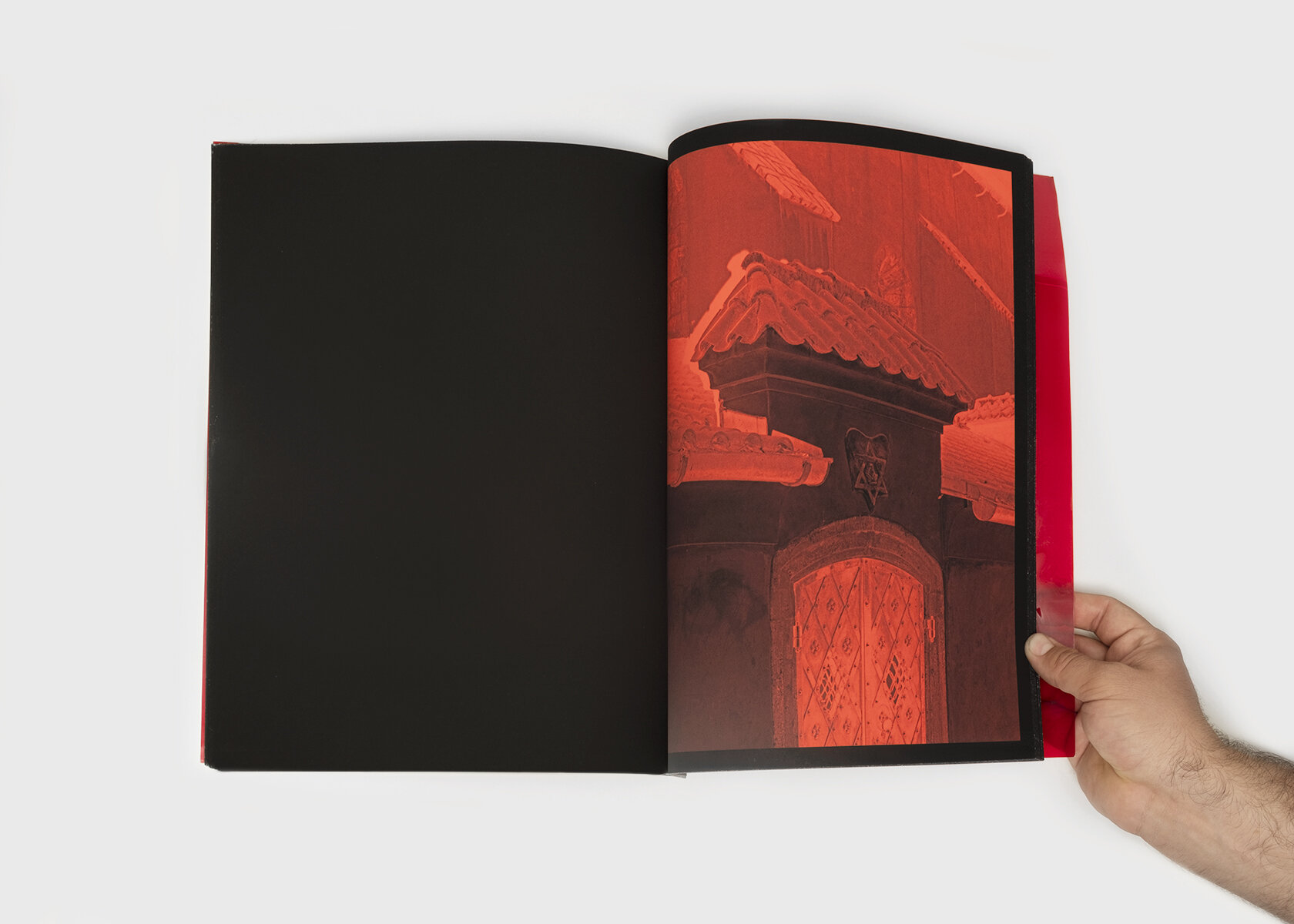

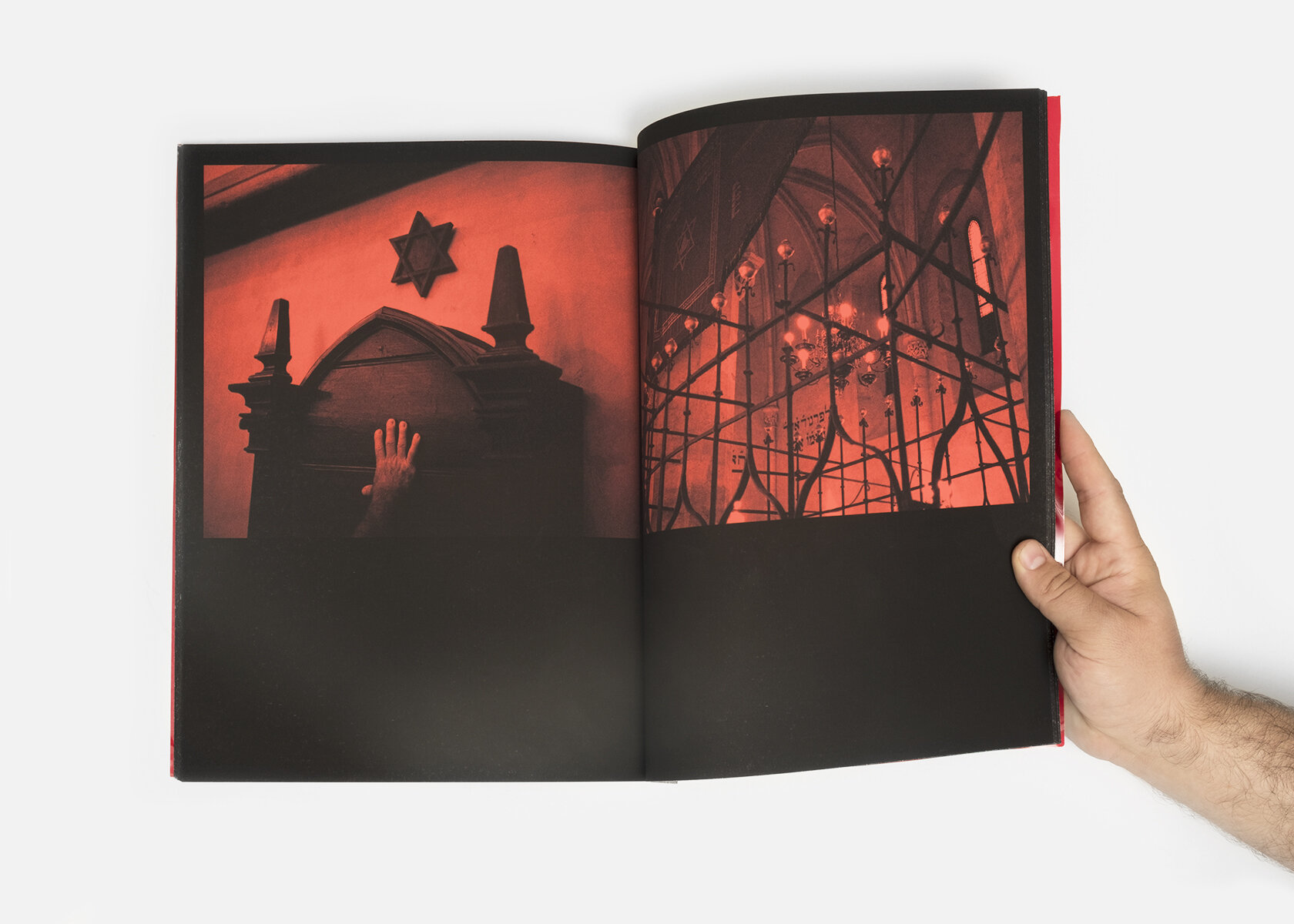

Beshert’s photographs of the empty, nocturnal, blood-red streets of Prague, seen through the eyes of golem/Freedman, convey a sense of seeking, and of intangible longing. Although the Josefov ghetto was demolished around the turn of the twentieth century, these contemporary images selectively depict street scenes and some of the gothic architecture still standing from the time of the legend’s conception—as the golem would have seen them—and yet their first-person photographic perspective creates a time slippage, cycling between the present and the past. Freedman sees the golem as his surrealist double; his adoption of its perspective enabled him to inhabit the myth, bringing it to life in his own manner. Informed by surrealist automatism, and engaging yet subverting the idea of the detached flâneur, the images alternate between positive and negative, and their tightly cropped views, skewed vantage points, and red colour impart the fragmented vision of a mind in turmoil. A moment of respite eventually comes in a photograph taken within the Old-New Synagogue, where we see the sole trace of a human body. A man’s hand, touching the place where the Rabbi sat, doubly signals the call to a higher power/father figure—the hand itself is that of the artist’s father.

The voyage closes on a flat, red, sunrise, silhouetting a darkened skyline. This image is paired with Freedman’s written response to his mother’s letter, in which he unites the fraught state of being “in the closet” with the golem’s own journey and symbolism. The two intensely personal letters bookend the wordless arc of the images, representing parallel realities invisibly woven together through time and space. Freedman’s powerful reframing of the golem myth underscores the dangers of believing in suppression or silence as self-protection, and highlights the essentially healing power of honesty and self-determination.